A Century of Impact

In this episode, Stanford GSB faculty reflect on the ideas, values, and community that have defined the school.

written by Michael McDowell

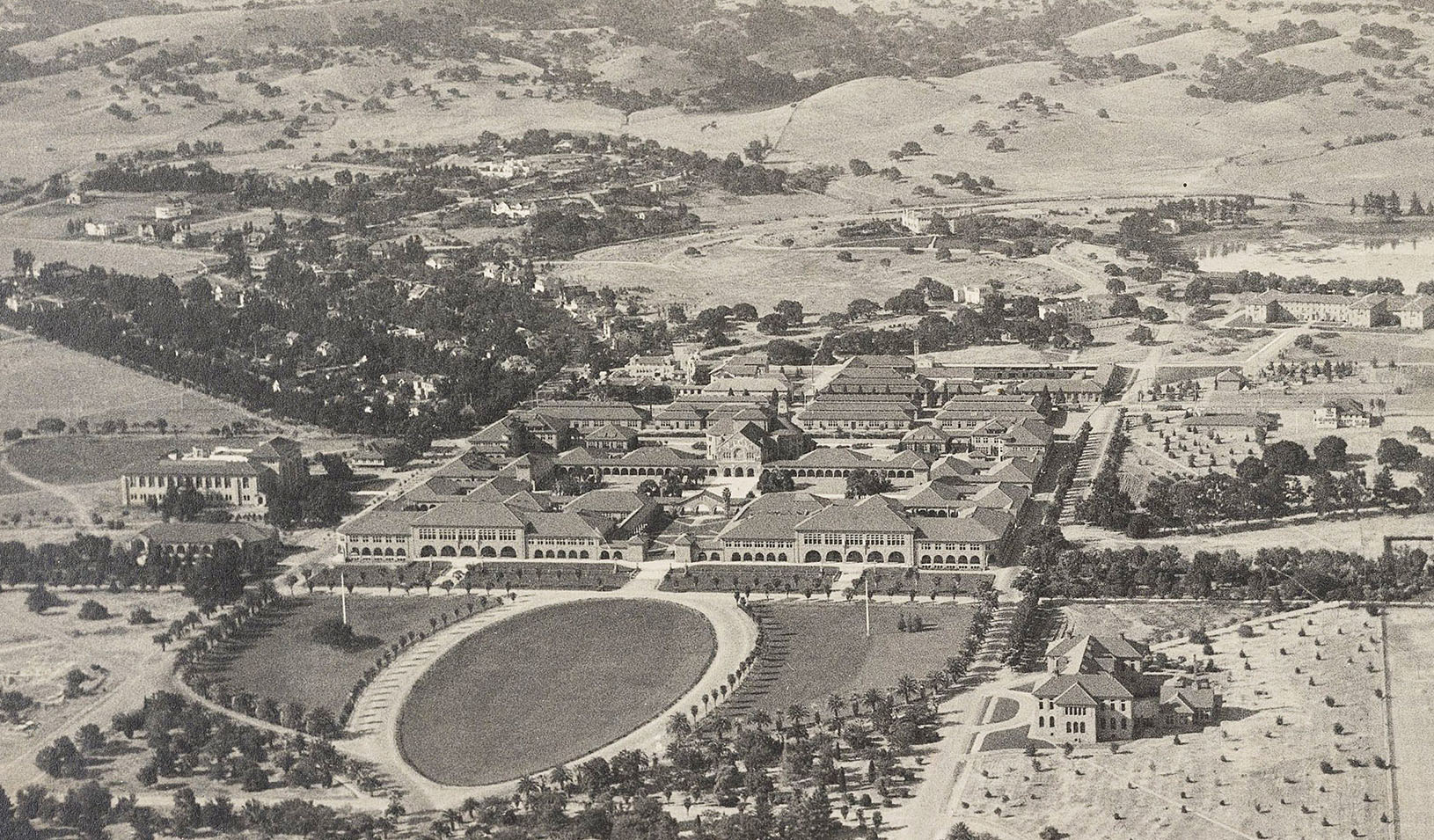

Back photo from GSB Archives

In 1925, Herbert Hoover, a Stanford alum and future U.S. president, had an idea. “A graduate School of Business Administration is urgently needed upon the Pacific Coast,” he wrote.

One hundred years later, what has Stanford Graduate School of Business accomplished, and what might its future hold?

“We are at the mecca of computational innovation,” says Amir Goldberg, a professor of organizational behavior. “We’re going through a revolution again with the introduction of AI. No university, no school is better poised to be the leader in understanding the implications of AI… than Stanford GSB.”

On this episode of GSB at 100, our faculty reflect on the ideas, values, and innovations that have defined the school, from its founding principles and pioneering research to its role at the frontier of technology and leadership.

“The magic here — and I will say it’s magical — is the simultaneous focus on humility, but also impact,” says Michele Gelfand, the John H. Scully Professor in Cross-Cultural Management and professor of organizational behavior.

Listen & Subscribe

Created especially for Stanford Graduate School of Business’s Centennial, GSB at 100 is a four-episode series that presents a scrapbook of memories, ideas, and breakthroughs as the GSB celebrates its first century and looks ahead to what the next hundred years may hold.

Full Transcript

Note: This transcript was generated by an automated system and has been lightly edited for clarity. It may contain errors or omissions.

Philip Lee: This is the Bass Library, and now we’re heading down to the, I call this the basement, but it’s not really the basement.

Kevin Cool: Down a spiral staircase, around a corner and through a quiet corridor, you’ll find a door that leads to the archives of Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Philip Lee: So this is the archive. It’s amazing to me that they still have these items. They have the original telegrams from Herbert Hoover just sitting in a box.

Kevin Cool: We’re in the basement of Bass Library and archivist Philip Lee is shuffling through old photographs, telegrams, and letters that tell the story of the school’s founding.

Philip Lee: To me, it’s like detective work. It’s like a cold case where you notice stuff there, there’s information and you have to try and piece it together. I think of the items, like some of the items here, they’re moments in time.

Kevin Cool: Moments that in some cases take us all the way back to 1925. Herbert Hoover, a Stanford alum and future U.S. president, had an idea.

Philip Lee: He realized that the young businessmen were going to Harvard to the business school, which opened in 1908, and it was floated at the time here that Stanford should follow Harvard and have their own business school. And he was thinking to himself, “We should really set up a business school because what happens is, when they go to the East Coast, they don’t come back.” So it was a brain drain and a talent drain.

Kevin Cool: Hoover wrote at the time, quote, “A graduate School of business administration is urgently needed upon the Pacific Coast.” End quote. Hoover proposed raising $50,000 to launch the new school, in his words, “experimentally for a period of five years,” and that is truly the beginning of the GSB.

Another document describes a mission. It quotes Jacob Hugh Jackson, a professor of accounting and an early dean at the school.

Philip Lee: “The goal of the school is to train our students to work effectively for themselves and the business of which they are part of, to imbue them with the spirit of service for their communities and society as a whole, and to develop in them the ability to live rich and happy lives. This is the goal of the Graduate School of Business.”

Kevin Cool: That sounds a lot like the school’s motto today, “Change lives, Change organizations, Change the World.”

This year, the Graduate School of Business celebrates its 100th birthday, and we’re making a podcast series to capture this milestone through the stories of the people who have shaped and continue to shape the GSB. You’ll hear from faculty, staff, alumni, and students in a kind of scrapbook of memories, hopes and dreams as we celebrate our first hundred years and look forward to the next.

Today we hear from six GSB professors. We ask them to reflect on the GSB’s impact over the past century and what will be important for the school to get right in the future. Their answers touch on founding principles, frontier technologies, and the ideas and values that make the GSB unique. Because what sets the school apart isn’t just research or rigor, it’s curiosity, humility and the sense that we’re contributing to the broader project of human progress. So let’s get started.

This is GSB at 100. I’m your host, Kevin Cool.

Jeffrey Pfeffer is a professor of organizational behavior who has taught at the GSB since 1979. Pfeffer says it’s the people — faculty, staff and students — that give the school its power.

Jeffrey Pfeffer: Many people believe that productivity is a consequence of ability times motivation. I don’t actually agree with that. I think it is ability times motivation, times your environment, that if you are smart and if you are motivated, but if you are surrounded by talent, you’ll almost by definition do better work. And by the way, you can see this in sports as well, where there are people who don’t necessarily score a ton of points, but they make everybody around them better. And you see this in this work environment as well. We are a people-based organization and the quality of the people makes the quality of the place. And that’s simply what has made the GSB what it is. And the fact that our brand has grown, which makes it easier for us to attract the best faculty and the best students, is of course extraordinarily helpful.

And going forward, I would say, I think it is extraordinarily easy to lose focus on what matters. It is easy to get diverted by revenues minus expenses, which is considered to be profits, even in a non-profit organization. It is easy to lose sight of the importance of the human capital element, and we are in the human capital business. It is easy to lose perspective on short versus long-term investments. The thing that makes leadership hard is not the evidence on what produces success, which is overwhelming and which frankly, everybody knows. So it is, in fact, this laser focus on the connection between human well-being, productivity, performance, profitability.

Kevin Cool: If Pfeffer points us toward people, Anat Admati reminds us of the values that guide them. Admati is a professor of finance who started at the GSB in 1983.

Anat Admati: So the GSB, from the period that I know it, and I’ve been here 41 years and a half, it’s a long time, has become, especially for the latter half of its existence, the example of an academic business school, which is highly respectable by the disciplines of the social sciences for the best quality research in various fields of the social science, and yet teaching future business leaders in professional programs as well as in a PhD program. So that was probably the crowning achievement.

What also happened, though, in the last 100 is we had one dean who I want to single out, and his name was Arjay Miller. Arjay Miller came to Stanford in 1969 and his condition for becoming the dean of Stanford Business School was that Stanford Business School admits 10% of the students to what he called the public management program, in which he thought that people who are going to be in the government, in the public sector should get the same education as we have the private sector so they understand what a balance sheet is and what’s going on, and they can have this expertise that sometimes people in government don’t have. And he really understood and appreciated the importance of good government. He said, for example, “The mayor of Detroit has many more problems than I have at Ford,” which is where he was the president. Then he gave a speech to academics in December 1968 that sounds like it could be given today.

Kevin Cool: We wanted to tell you a little more about Miller’s speech. He delivered it on December 29, 1968, in the final days of a turbulent year of anti-war protests, urban riots and the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. At the time, Miller was also a vice chairman of the board of Ford Motor Company. We don’t have audio or video of Miller’s speech, so I’m going to read some of it.

“There can be no doubt about the magnitude and gravity of the present challenge to our free society. The task we face is both awesome and urgent, but there can be no doubt on the other hand of our power to meet our problems and achieve a better society. Having that power, we have also an obligation to recognize the challenge and the opportunities and to make a beginning. Let us not fail to use all of the vision, goodwill and power at our command.”

Arjay Miller, December 1968. Now back to Professor Admati.

Anat Admati: I did speak with him when he was already 100 years old and very clear-minded, and he knew what we needed to do, which I believe we should be doing, which is, again, step into the big picture and see where we and our students fit in and try to integrate ourselves in the broader societal issues as opposed to only teach our students these essentially techniques for succeeding in the private sector.

Kevin Cool: From values to breakthroughs, Professor of Economics, Susan Athey, describes pioneering work in market design that changed the world as well as frontier research in machine learning that continues to change it.

Susan Athey: The GSB has had so many impacts, but let me just pick one particular issue that’s close to my heart, which is that it’s been several times in its history, it’s really been on the frontier of important ideas. One of the big ideas in the group that I’m in was market design and the use of formal strategic thinking and game theory and information economics to understand real phenomena. And Bob Wilson, who’s one of the grandfathers of the group that I sit in, Economics, he worked with oil companies in 1960s and looked at their bidding data and then developed formal theories that helped understand what was going wrong in those markets and how to fix it. And then later, he advised one of my advisors, Paul Milgrom, and they shared the Nobel Prize for some of their work on market design.

And so, there’s many different takes on that, but one of my takes was that there was the connection to the world and the fact that the problem they were solving was coming out of a real problem leading to cutting edge theory that then created a field that didn’t exist. More recently, we were on the cutting edge of using machine learning for decision problems and what’s called causal inference, formally, and now Stanford is the best place in the world to do this kind of research. To go from zero in 2012 to best in the world with multiple amazing young scholars doing cutting edge research in 12 years is really stunning. And the GSB really supported us in that endeavor.

So I think the GSB has been a really fabulous place for helping us stay grounded and really connected to real problems, but also allowing us to hire the kind of talent and giving us the space to do the pure research that doesn’t just solve today’s practical problems, but that actually builds the foundation for many people to solve applied problems.

Kevin Cool: The GSB has long been a place where theory meets the real world. Matteo Maggiori, professor of finance, connects formulas developed here, which today bolster markets worth trillions of dollars, to a new wave of economic inquiry made possible by the power of AI.

Matteo Maggiori: Let me start from the history and in particular the history of, I guess, the field that is closest to me, which is finance. Bill Sharpe, who’s a Nobel laureate, is certainly a big figure in the history of the school and the development of what are called equilibrium models of asset pricing. The basic models and how the entire industry works on has been developed by Bill together with other academics.

Similarly, Myron Scholes is one of my colleagues, is one of the inventors of the option pricing formula. We have trillion dollars worth of derivative markets that exist today that would probably not have existed had it not been for those discoveries that told us how to understand those risks, price these derivatives. Essentially, they were really instrumental in creating a market for these instruments. Those are incredible achievements by any intellectual standard.

If I look at the next 50 years, now, one of the things that has certainly happened throughout many fields, but certainly in economics and in finance, is the advent of very large data. We can measure things or have a look at economic relationships around the world that 10 years ago would’ve been impossible. Computing power has expanded enormously. Right now, we’re seeing a wave of artificial intelligence on large language models that, again, 10 years ago would’ve been hard to imagine. And we should jump, as a school or as an intellectual enterprise, into the leadership of these developments. To me, they fit the bill of incredible intellectual pursuits that, at the same time, clearly have a very large impact on the real world. And that’s a great space for GSB to be in.

Kevin Cool: As Maggiori explores how new technologies could transform our understanding of markets, Amir Goldberg, a professor of organizational behavior, evaluates how they’re already being used in business and government. Goldberg believes that the GSB is uniquely equipped to help future leaders deliver on the enormous promise of AI.

Amir Goldberg: So I think what makes the Stanford GSB unique is that it has always resisted the temptation of giving simple recipes and one-size-fit-all war stories. And we have always been at the forefront of analytical thinking and research-driven insight, or at least that’s how I see the GSB. We’re not in the business of solving our students, our MBA students, our participants in executive education programs, we’re not in the business of giving them simple, practical advice about how to solve their problems. We are helping them think about the world in analytical ways that will become analytical instrumentation for them to become better leaders and better managers. And we have often resisted the temptation of quick fixes and always invested in fundamental social scientific innovation. I think that’s been, at least in the 13 years that I’ve been here, and probably the few decades that preceded that, I think that has been our differentiating characteristic.

In terms of the second question of what the GSB needs to get right in the future, we are at the mecca of and have been for 40 years of computational innovation. We’re going through a revolution again with the introduction of AI. No university, no school is better poised to be the leader in understanding the implications of AI, the ability to use it and harness it as a managerial, as a productivity tool than the Stanford GSB. And I think our role is to educate our students how to think with and through data and predictive and generative AI as tools. And I’m very excited about that. I think we are definitely taking on this challenge. We’ll get a lot of things wrong, for sure, but hopefully we’ll produce some insights that will be useful.

Kevin Cool: Whether the professors you’ve heard so far are talking about people, purpose, research, innovation, or leadership, what connects these reflections is something harder to define. Michele Gelfand, a professor of organizational behavior, describes that intangible thing that gives the GSB its character.

Michele Gelfand: The magic here, and I will say it’s magical, is the simultaneous focus on humility, but also impact and trying to really change… That’s the logo, change people, change organizations, change the world, but the humility that goes with that is just astonishing. And I would say also just the level of curiosity at the GSB combined with that humility is really amazing. So it’s a very magical combination of having humility, curiosity and impact. And so I guess I would say that I would just want to keep those elements to this place because I don’t think they’re found together in any one place that I’ve been in. We’re kind of an ambidextrous place. I think there’s certainly a lot of sense of creativity and question and move fast and these kinds of things. But there’s also a sense of accountability that we have a mission, that we have to contribute something to the world and leave the place a better place that I think our students and faculty, there’s that secret code that unites us.

Kevin Cool: One hundred years from now, someone might find this episode in a digital archive. What will they hear in our voices? What will they imagine about this moment in time and about the people who lived it?

The GSB was founded with a simple but ambitious purpose, to train leaders who could serve society.

One hundred years later, that mission still holds, but so does something else. The belief that progress depends on people willing to question, imagine and build. And if the past is any guide, the next 100 years will produce ideas we can’t yet see and leaders whom we haven’t yet met. That’s the promise of this place: not that we know what’s next, but that we’re creating it together.

On our next episode, we’ll hear from the people who help make it all possible, members of the GSB staff.

Courtney Payne: At some point, I will eventually retire from this place, but I’m still going to be in my head and my heart part of it, and I know I can always look to the GSB to understand what’s coming next.

Kevin Cool: A special thanks to all those who made this podcast possible, and thank you for listening.

Philip Lee: So last week, it was the 19th of July, 2025, and the letter I was getting scanned was the 19th of July, 1924. And I’m like, “Wow, I wonder if that person who was writing the letter at that day would know that, in 100 years time, there’d be an Irishman in Stanford looking at this letter.” You know what I mean? It’s so weird when you think about it.