- Changing Lives

Five Stanford GSB Deans on Culture, Challenges, and Enduring Values

Written by Michael McDowell

A panel discussion at the school’s Centennial celebration featured the accumulated wisdom of 35 years of deanship.

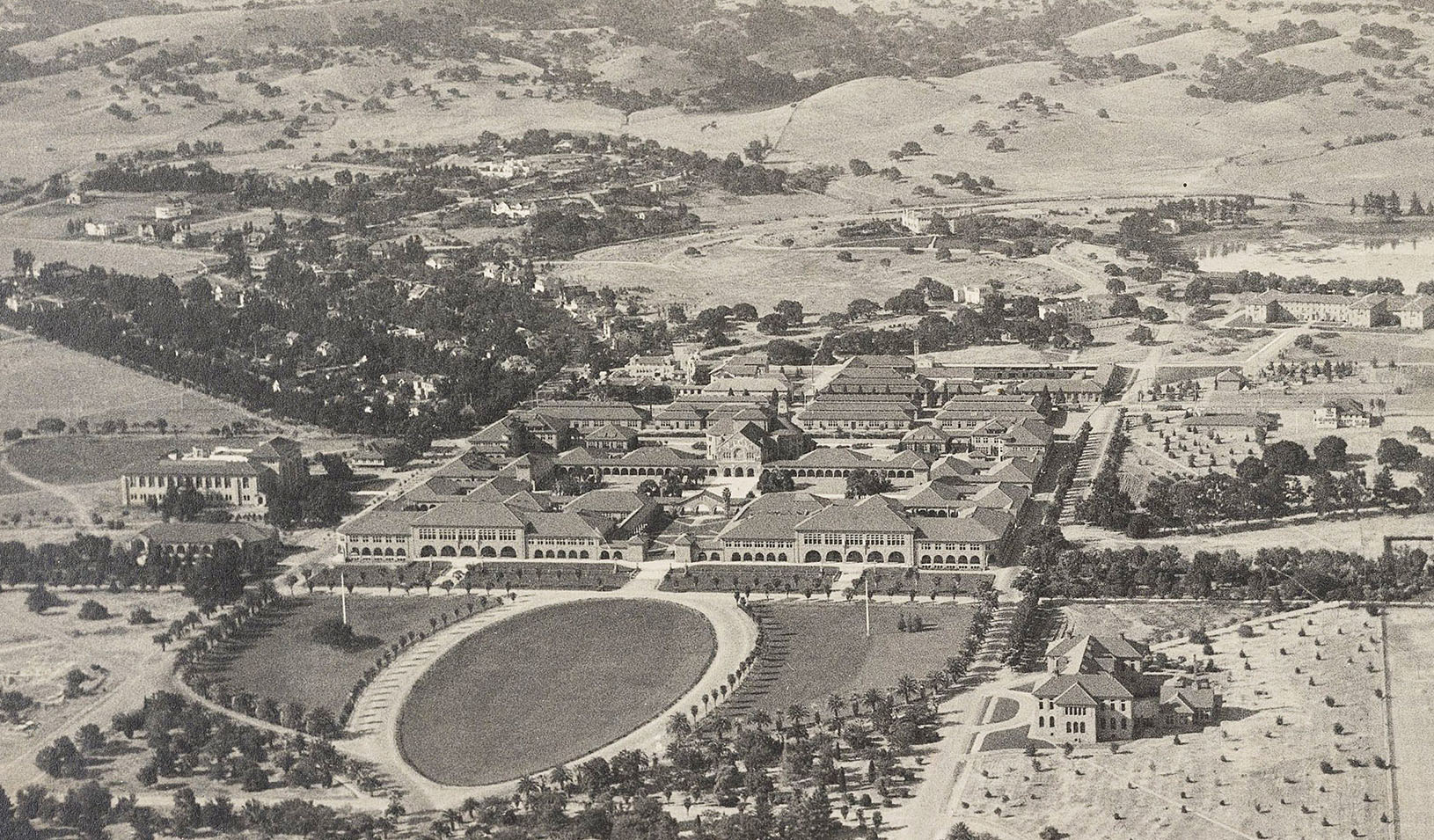

On October 10, Stanford Graduate School of Business marked its Centennial with a full day — and night — of celebration. More than 3,200 alumni, students, faculty, and staff converged on campus for programming that reflected the spirit of the GSB and provided an occasion for conversation, connection, and community building.

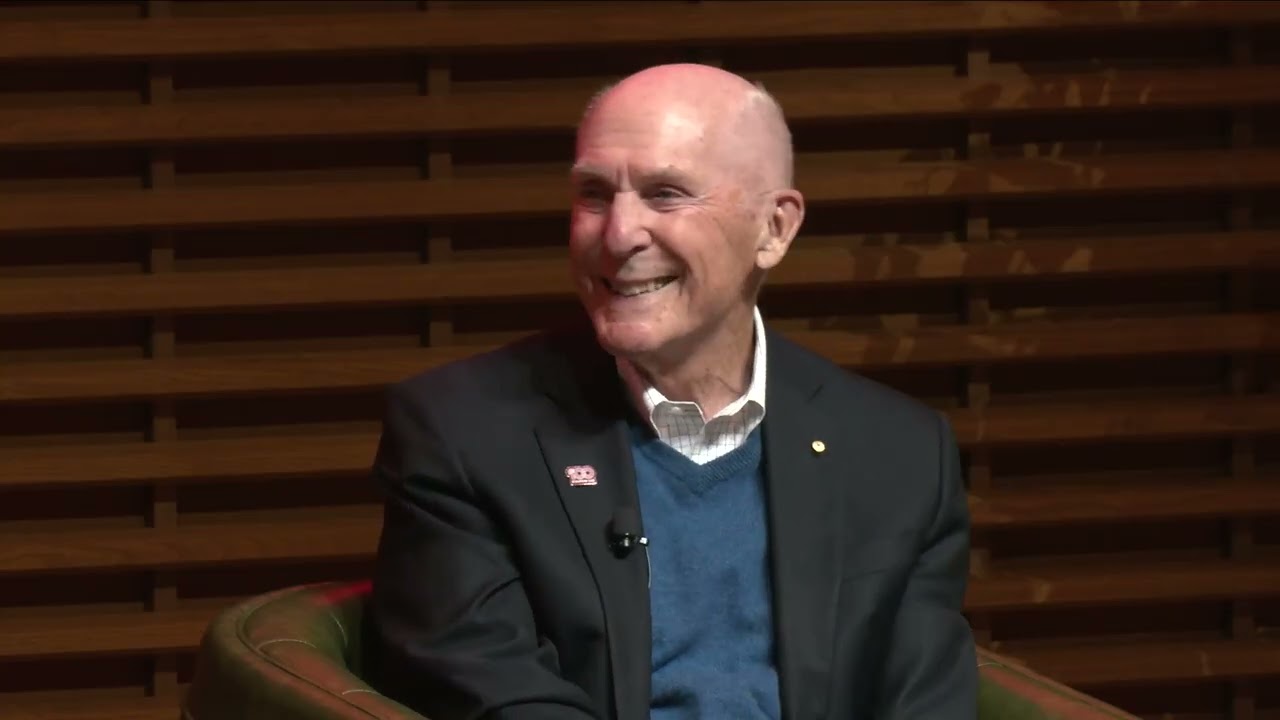

One panel featured all of Stanford GSB’s living deans — Sarah A. Soule, Philip H. Knight Professor and Dean, and Morgridge Professor of Organizational Behavior; Jonathan Levin, president of Stanford University and Bing Presidential Professor; Garth Saloner, PhD ’82, Botha-Chan Professor of Economics; Robert L. Joss, Sloan ’66, MBA ’67, PhD ’70, Philip H. Knight Professor and Dean, Emeritus; and A. Michael Spence, Philip H. Knight Professor and Dean, Emeritus.

It was a rare opportunity to hear the perspectives and stories of the leaders who have helped shape Stanford GSB for the past 35 years. Joked moderator Roelof Botha, MBA ’00 and partner at Sequoia Capital, “It’s not often that a student gets to cold-call the professor, let alone the dean, let alone all five.”

The wide-ranging and thoughtful discussion addressed a few recurring themes — including the importance of community, the value of continuity, and the nature of principled leadership — as well as shared memories, a commitment to tackling present-day challenges, and even a few laughs.

A Shared Legacy

Spence, whose tenure began in 1990, set the tone.

“When I came to the school, the group of people that created the foundations of this great institution were still here,” he said. “Everybody knows about Ernie Arbuckle and Arjay Miller, but there were others. One of them is sitting here: George Parker,” he noted, prompting applause. “It was Lee Bach, Jim Van Horne, Chuck Holloway, Chuck Horngren — they were my tutors. They taught me what this place was all about, how they built it, and what its culture really meant.”

Knitting together the diverse groups that compose this unique culture is no easy feat.

“I think the biggest challenge in this job, and maybe everyone would agree, is connecting with and bringing together in common cause all the multiple constituents that make up the GSB community,” said Joss, who took over in 1999. “We want them all to appreciate each other and understand the vital role each one plays… it’s a team effort in many respects.”

Saloner succeeded Joss in 2009.

“The first thing you want to do as dean is get your timing right, and following these two guys” — Spence and Joss — “we could hardly go wrong,” Saloner quipped. “When I became dean, we were well on our way to being the destination of choice for young men and women who wanted to do an MBA degree. During the next few years, we accomplished that. So then the question is, okay, where do you go from there?”

Embracing entrepreneurship — without letting it come to define the school — would be key, Saloner recalled, spurring initiatives like the Center for Entrepreneurial Studies, the Venture Capital Initiative, Stanford Ignite, and Stanford Seed.

Meeting the Moment

Levin, dean of Stanford GSB from 2016 to 2024 — when he became president of Stanford University — recognized the consequential role of universities.

“The model that we have at universities of basic research, of science, and of innovation, it is the most powerful engine in this country for economic growth and, ultimately, jobs and leadership,” he said. “Stanford is the exemplar of that more than anywhere else on the planet,” he added, noting that the technologies that underpin the current boom in artificial intelligence were developed in part through National Science Foundation-funded research that took place at Stanford.

“This is something that academic institutions do in a way that no one else can do, and it’s so important to preserve,” he said. Ultimately, sustaining that model will depend on a community that remains engaged, values-driven, and united in a shared purpose. “If you set the right principles and you get a great group of people working on it — and you put in the work — often you can turn that into something really spectacular.”

Soule, the first woman to lead Stanford GSB, succeeded interim dean Peter DeMarzo in 2025. She described two of the principles that guide her leadership: excellence and community.

“Excellence is obvious: It’s Stanford,” she began. “The second is community. I always talk about the community that this place has given us all — alums, faculty, staff, students — and how that’s an enduring characteristic we want to preserve.”

Doing so, in part, she continued, requires cultivating curiosity and generosity. “Our faculty, our students, our staff, and our alums are at their very best when they’re allowed to be curious, when they’re trying to satisfy that curiosity by asking good questions and diving into data and debating and discussing with each other,” she said. “The other is generosity. We are at our best when we are generous with our ideas, our time, our energy, our resources, and when we give each other grace when we disagree with one another.”

Into the Future

Audience questions pushed the panel toward the horizon, from AI to the evolving role of business education. Asked about the importance of investing in human capital in the face of existential technological disruption, Spence pointed to the role of human judgment in shaping technological progress.

“These things are neither good nor bad by themselves,” he said. “If you read the [United Nations] Human Development Report, it makes one incredibly important point… it basically says this is a choice. We’re not just watching something autonomous take over. It’s choices that we make,” he continued. “I think it’s a mindset that the business school can help manage.”

Such a mindset underscores the continuing relevance of a sound business education, and Soule said she believes empowering students to see themselves as agents of change is central to preparing future leaders for the complexities they will inevitably encounter.

I think the biggest challenge in this job… is connecting with and bringing together in common cause all the multiple constituents that make up the GSB community.

— Bob Joss

“We do an extraordinary job of teaching all of the people who come to us, from whichever population, that as a leader they are embedded in a very complicated context,” Soule said, echoing the organizational behavior courses that influence so many Stanford GSB students. “We teach them that these are never aligned, and that it’s not enough to just be aware of what these complicated factors are. [Students] have to both be able to navigate this context with courage and they need to be inspired to try to change this context when it needs to be changed.”

Anchored in agency, awareness, and responsibility, this approach is embedded in the Stanford GSB curriculum, Soule concluded. “Often we don’t talk about that as leadership, but it is something that I feel very deeply that we provide people, and I think that will be what’s needed in this particular moment, too.”