“Learning Here Isn’t Just About Ideas”

From management to modeling, we explore the classroom experience at Stanford Graduate School of Business on GSB at 100.

written by Michael McDowell

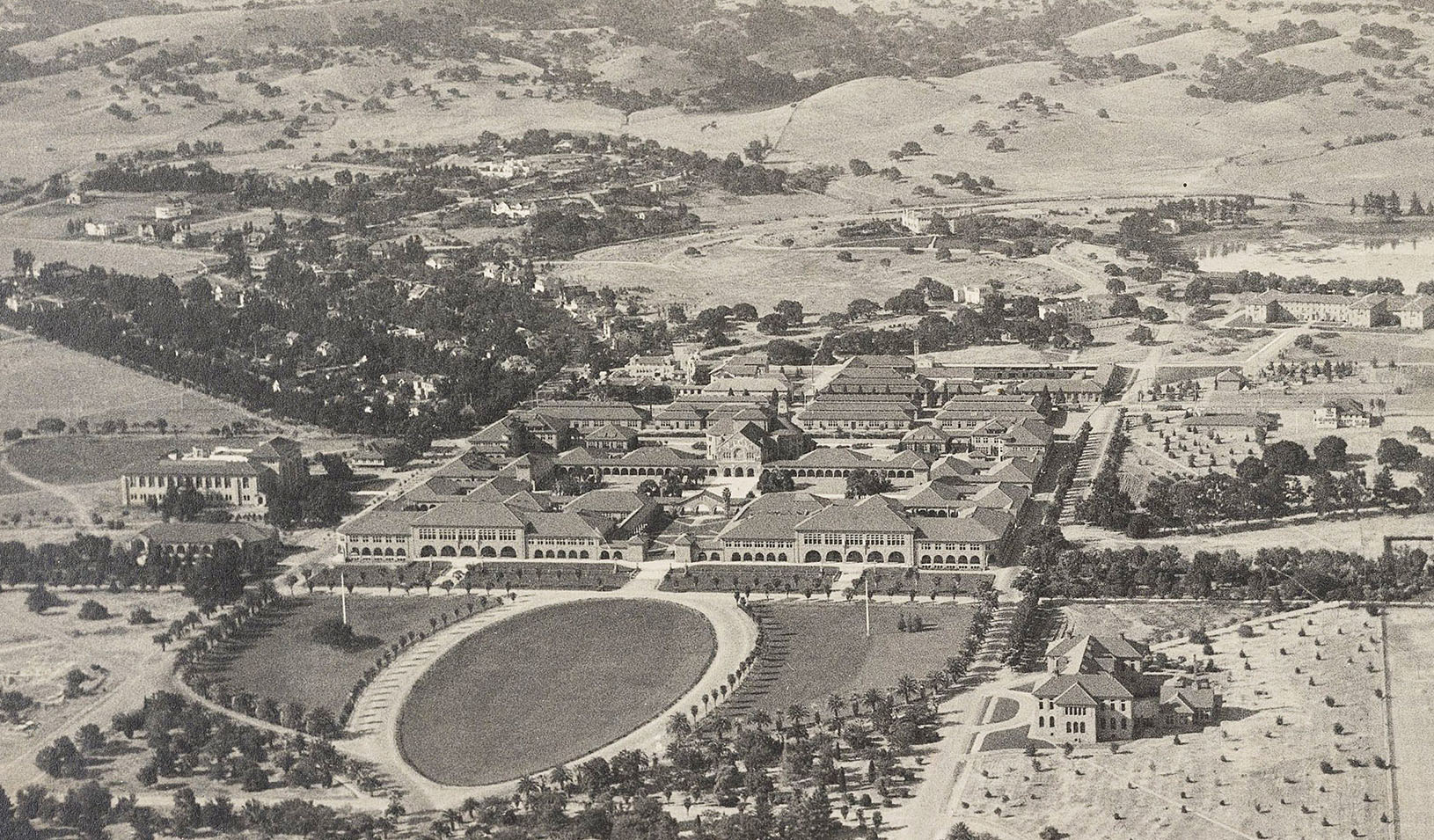

Back photo from GSB Archives

Transformational teaching takes many forms at Stanford Graduate School of Business. For Professor Ed deHaan, the true impact of teaching the core accounting class doesn’t show up in the classroom. It appears years later, when former students find themselves leading teams, sitting in boardrooms, or translating high-level decisions into financial statements. “What I really hope,” deHaan says, “is that somebody thinks, ‘This was a challenging class. I enjoyed it. I learned something.’ But much more importantly, 10 years later, they look back and think, ‘That was worthwhile.’”

In Interpersonal Dynamics, known to generations of MBAs as “Touchy Feely,” lecturer Andrea Corney, JD/MBA ’90, teaches students effective communication. “It’s a profound shift in how people see themselves and their relationships,” she says. “Realizing that how my relationships are going is not some strange mystery that I have no control over. It’s like, ‘Wow, my behavior has a huge impact on other people. I have choices.’”

Economics professor and former dean Garth Saloner creates immersive experiences in his entrepreneurship and strategy course. Students spend one day dissecting a case and the next debating it with the founders and investors featured in it. “At Stanford, just another day,” Saloner says.

On this episode of GSB at 100, you’ll hear from professors and lecturers who challenge, inspire, and prepare students to lead in a demanding, complex, and rapidly changing world. “Learning here isn’t just about ideas,” says host Kevin Cool. “It’s about what those ideas make possible.”

Listen & Subscribe

Created especially for Stanford Graduate School of Business’s Centennial, GSB at 100 is a four-episode series that presents a scrapbook of memories, ideas, and breakthroughs as the GSB celebrates its first century and looks ahead to what the next hundred years may hold.

Full Transcript

Note: This transcript was generated by an automated system and has been lightly edited for clarity. It may contain errors or omissions.

Christian Wheeler: Hey, everybody. I’m Christian Wheeler. I’m a marketing professor here. We’re not going to talk about marketing today.

Kevin Cool: We’re sitting in on a class called “Creating Something From Nothing.” It’s part of Stanford Graduate School of Business’s Executive Education Program.

Christian Wheeler: This is going to be a 30,000-foot view of what the creative process is like. I know that a lot of you may not be doing the creative heavy lifting in your organizations, but you’re going to be managing some of the people that do that.

Kevin Cool: Most of the 50 or so students are executives at businesses and nonprofit organizations from many different countries. Christian’s class is one piece of the six-week intensive program. About halfway through, Christian asks his students to get out of their seats.

Christian Wheeler: We’re going to play a game called Three Things. Can I have a quick volunteer to come up and demonstrate it with me? It’ll be super easy.

Students: I’ll go.

Christian Wheeler: Excellent. Give [student] a round of applause.

Kevin Cool: Three Things is an improv game played in small groups. First, one member of the team chooses the category. Then, another member tries to quickly say three items in that category.

Christian Wheeler: This is very important. I want you to strive for speed rather than accuracy…

Kevin Cool: It sounds like this.

Christian Wheeler: Let’s start with the beginning.

Students: Three Things.

Christian Wheeler: Three things that are red.

Students: Apple, cherries, raspberries.

Christian Wheeler: Fantastic. Let me say three things —

Students: Three things.

Christian Wheeler: And then you give me a category. It could be any category with three or more things.

Students: Three animals.

Christian Wheeler: Three animals. So I say cat, dog, elephant.

Students: Three things.

Christian Wheeler: Three things. And I might say, three things that make you happy.

Students: Beer, sake, and … [laughs]

Kevin Cool: The students break into groups and the game begins.

Students: Three things. Three things of sports. Three things, running, jogging, walking. Three things. Three things. Three gems. Gems? Three gems. Okay. Is diamond a gem? Yes, yes, yes. Diamond is a gem. I don’t know gems. A diamond, silver, copper. I don’t know. I don’t know.

Kevin Cool: Christian brings everyone back to their seats and explains how the immersive game illuminates a key principle of creativity.

Christian Wheeler: So if I were to give you one piece of advice, here’s the thing to write down. If you want a good idea, come up with a lot of ideas. More ideas equals better, best idea. It’s just true. And when you think you’re done, you’re probably not done. You have more ideas and often our best ideas come later than the sequence.

Kevin Cool: Whether the subject is the creative process, or, as you’ll hear later in the episode, accounting, optimization, ethics or leadership, GSB professors employ a diverse range of teaching methods to transform abstract ideas into vivid learning experiences. And no matter the subject, student engagement is key.

Speaker: I think what Stanford, I feel they do it really well, is not just pure academics. They’re very good at connecting us because I have a large team. I find that very applicable that I can take it to my team. You energize just a little bit of this and then everybody has positive thinking, and I can continue with a more, I think, better discussion.

I would’ve commented early on we started off as colleagues. I consider a lot of these people friends now because of what we’ve shared and how much we’re interacting, and it’s creating mind unlocks for a lot of us.

Kevin Cool: Over the past 100 years, the GSB, which began as an experiment on the Pacific Coast, became one of the most influential business schools in the world. A place where students of all kinds developed the skills to change lives, organizations and the world.

Every term and across each of the school’s seven academic areas, professors, lecturers, and practitioners bring knowledge to life, challenging, inspiring, and empowering the next generation of leaders. The GSB’s ideas, values, and people intersect in the classroom, and that’s where we’re taking you today.

This is GSB at 100. I’m your host, Kevin Cool.

After class, we caught up with Christian.

Christian Wheeler: A lot of the creativity stuff that I teach is this in-the-moment, creativity. So you could think of long-term creativity, like we need to figure out a new market for some offering of our company in the next five years. Or you can think of like in-the-moment, creativity. You’re engaging in a Q&A in front of a bunch of angry investors. How do you handle these difficult questions? Those are two very different types of processes potentially.

But I think that latter thing is also very important, that the future is inherently unknowable. Our environments are increasingly unpredictable. The world is changing at an ever faster rate, and you never predict the future, whether it’s five years in the future or just how this podcast is going to go. Things are different than I expected they would be. They always are. But you need to be able to adapt in that moment and to come up with creative solutions to give an appropriate response in that situation.

Kevin Cool: From the degree programs to executive education, GSB, professors blend creativity, rigor and purpose in teaching. Their students include MBAs, PhD candidates, experienced professionals, undergraduates, and even global entrepreneurs.

Suzie Noh is an assistant professor of accounting who was recently recognized for her teaching in the Master’s of Management program.

Suzie Noh: Students have this perception that accounting is a boring subject, which it is. But what I try to emphasize is that it is a form of communication. It is a way for companies to communicate with outside stakeholders, including competitors, regulators, investors, or the society at large. Behind every number are the decisions made by managers, and so once you start to link accounting to ethics and business strategy, it becomes more dynamic. And so once students start to see accounting that way, I think they start to ask deeper questions. And one way to facilitate that is to use real company’s financial statements.

I pull out Meta’s financial statements and it sparks great discussions about how to measure the value of a company when the business is built around just users, networks and ideas. When I cover fixed assets and impairments, we pull out Disney’s financial statements and I ask, “How would you measure the impact of COVID-19 on business amusement parks?” Because students recognize these firms and their products and some of the students even have worked for them, the learning becomes very personal, and they can start to link the accounting questions back to the company’s business model or the objectives or the type of competition that they face, and that’s when the class starts to become super active and fun.

Kevin Cool: Real world examples not only serve to illuminate complex material, but prepare MBA students for the challenges they’ll face long after they graduate.

Ed deHaan: I’m really thinking, what is going to make this group of students as successful as possible not this quarter or even in their two years here at GSB, but five, 10, 15 years down the road? What I really hope is that somebody thinks, “This was a challenging class, I enjoyed it, I learned something.” But much more importantly, 10 years later, they look back and think, “That was worthwhile.”

Kevin Cool: That’s MBA Class of 1963, Professor of Management Ed deHaan.

Ed deHaan: So accounting really is the language of business. The further you get up in an organization, the more important it is to speak that language. So when somebody starts out, maybe they’ve just left GSB and they’re in a product manager role, maybe they don’t need to be interacting with the firm’s financial statements or financial reporting on a regular basis, not at that level. But as they move up five years later say, when they’re starting to get into quite senior roles, then it’s all the more important that they can take what they’re doing in their group and translate it into this unified language that we talk about in boardrooms or at the executive level.

We talk in terms of assets and liabilities and revenues and expenses and forecasted financials. So really much of the benefit they might get out of my class won’t come to full fruition until five years out. They might find themselves on day one in their job thinking, “Gosh, I don’t really on a daily basis think much about the balance sheet or income statement of my company.” But they will eventually reach a stage where that’s front and center in their mind, and that’s when I really want them to be able to look back on their GSB experience and think the rigor that they got day one in that first quarter accounting class is now really paying off down the line.

Kevin Cool: Eventually, some of these students may return to the classroom as practitioners. This is Botha-Chan Professor of Economics and former Dean, Garth Saloner.

Garth Saloner: I teach a class that combines my previous classes on entrepreneurship and strategy, and we put them together. In this course, it’s taught very much GSB-style, so it’s basically a case a day where we bring the protagonist of the case into class. So next week, for example, on Monday we will together have a discussion about a DoorDash case that I wrote a couple of years ago. And on Wednesday, the founder, Tony Xu and his investor from Sequoia, Alfred Lin, will both come to class, and the students will have an opportunity to have a discussion with them about the issues that we had discussed on Monday. So at Stanford, just another day.

Kevin Cool: From immersing students in decision-making scenarios to building complex models, a commitment to solving real-world problems is a foundational element of the GSB learning environment.

Dan Iancu, an Associate Professor of Operations, Information & Technology, teaches another piece of the core curriculum: Optimization and Simulation Modeling.

Dan Iancu: It’s really adopting a way to approach any kind of problem. This could be a business problem. It could be just a societal problem, a problem you face in your day-to-day life. And the approach entails being data-driven on the one hand, so trying to be quantitative, trying to measure as much as you can. The class then talks about modeling. So the modeling part is how do you take that messy problem and convert it into something that is reasonably formal? So how do we formalize a decision, and then how do we optimize it? How do we come up with the best decisions that are consistent with the constraints that optimize the objective? That’s the thing that we try to teach the students.

Kevin Cool: Teaching this approach to problem solving has become more complicated in the age of AI, and in Dan’s view, it’s all the more important ways that students understand why and how the machines deliver the results they do.

Dan Iancu: If you don’t understand, you don’t know how to do the model yourself or how to write the code yourself, you cannot evaluate. You can never quite know if those are the correct assumptions or if it’s the right prioritization.

Kevin Cool: But it isn’t only about being able to check your work.

Dan Iancu: How can the students remain in charge and not delegate everything to the chatbot and become powerless? I am more or less helping them maintain their job because all they do is pass something to the chatbot and take the output from the chatbot and give it back to whomever posed the question, their role becomes minimal. You need to remain really important in a decision process or in an organization. So in that sense, you have to have the human in the loop making some of these decisions. It’s the responsible way to use the tools.

Kevin Cool: Suzie Noh, who you heard from earlier, faces similar challenges in her classroom.

Suzie Noh: It’s so incredible just to think how different the world is now, even just compared to five years ago. The tools and the data the students have are just so different. So I think of it as a calculator. When a student are trying to learn math. Of course they can use calculators once they understand the underlying logic, but when they’re first understanding the mechanics of math, they first have to understand it right. So I allow them to use AI as a search tool, but I don’t allow them to fully rely on it when they’re first trying to understand how accounting works.

Kevin Cool: As technology transforms how decisions are made, it’s important to ask the question, what principles should guide the people or the machines making them?

Ken Shotts: Well, I think that good intentions are things that people have as individuals, and I think it’s things that business leaders talk about having for their organizations in terms of behavior within their organization. And it’s something that business leaders talk about their companies having in terms of effects on society as a whole. So there’s different levels that I think of and I think about good intentions.

Kevin Cool: That’s Professor of Political Economy, Ken Shotts, who along with his colleague Neil Malhotra, teaches “Leading with Values,” the GSB’s core class on business ethics.

Ken Shotts: So I think at an organizational level, it’s both the incentive structures and the informal norms and authority. So it’s the formal and the informal aspects of the organization, and that’s anything that the leaders of the organization are setting up. So that can include compensation systems. It can include who is promoted, how you make those decisions. It can include systems that are used to monitor what our people are doing.

It also includes what’s celebrated in an organization, what’s honored and held up is this is what we’re about. At a societal level, I really think of a lot of things outside of companies like legislative bodies, regulatory bodies, all those things that are government and also civil society as well. But those things that place limits on and that really can channel the amazing, productive, innovative, and efficient energies of capitalism in ways that are broadly beneficial for a lot of people. And I think a lot of people in business that have talked about is like, “Oh, this is just going to naturally happen. Just we’re going to go out and we’re going to make the world a better place.” It’s like almost a trope. It is a trope at this point. But the idea is like, well, if you want to actually have the world be a better place, you need to have the things that channel all that.

Kevin Cool: It’s about learning to lead with values, which can involve difficult conversations, active listening, and communicating with others whose belief systems may be at odds with your own. That points us to one of the GSB’s most popular and distinctive electives, “Interpersonal Dynamics,” which students dubbed “Touchy Feely.”

David Bradford: So the fascinating thing is the learning comes not from the facilitators or the instructor. The learning comes from other students.

Kevin Cool: David Bradford, who is a retired senior lecturer, co-created the course. What do students learn in one of the school’s most unusual classrooms?

David Bradford: They learn a set of competencies. They learn how to ask open-ended questions, to be empathic, to give behavioral feedback, to be in touch with their feelings, to communicate in a more congruent way. I think more importantly, they learn how to learn. They’re able to build relationships which are more open, trusting, and which use these competencies to build the sort of relationships they want. For some students, they are deep and intense with friends and family. With others, they are cordial. But hopefully all of them meet their needs and all of them are authentic in an appropriate way.

Kevin Cool: Andrea Corney, who took Interpersonal Dynamics with David when she was an MBA student, is a lecturer in management, and the faculty lead for Interpersonal Dynamics today. We spoke to the two together.

Andrea Corney: I think it’s different for different people. But at a very high level, it’s a profound shift in how people see themselves and their relationships, and that it’s that shift that I think is so transformational. And it will involve different things for different people. This realization that, oh, being more human, sharing more of my foibles, vulnerabilities, imperfect parts when done appropriately, actually brings people closer to me and has them like me more than pushing them away. For some people, that just blows their minds. For me, when I took the class, and I hear this from a lot of students, realizing that how my relationships are going is not some strange mystery that I have no control over. It’s like, “Wow, my behavior has a huge impact on other people. And then on my relationships. Oh my gosh, I have choices.”

Kevin Cool: For many students, the impact of Touchy Feely extends far beyond their time on campus.

David Bradford: We have people who say, “It saved my marriage.” “It saved my job.” “It may be a better person.” That’s tremendously rewarding, because what we know is that not only have we affected that person, but particularly with our business school students, they’re going to be affecting other people. They’re going to be better leaders. They’re going to be better human beings. In fact, we had one student who said, “I could have gone to many business schools. I could have learned a lot about leadership, but I came to Stanford to learn to be a better human being, and because of that, I know I’ll be a better leader.”

Kevin Cool: The idea that leadership begins with humanity and humility is central to the course, and perhaps also to the GSB itself.

David Bradford: I think the world is increasingly becoming a world of relationships, that organizations are held together by the network of relationships that people build, not by the organization chart. As the world is becoming much more complex, multicultural, we need the skills of how do I build relationships that are meaningful in a relatively short period of time with people who are very different than me? And I think that that’s why this course and the work that it’s built on is going to become increasingly important.

Kevin Cool: It wouldn’t be possible to cover the breadth of what’s offered at the GSB in a single podcast episode, but today we’re trying to give you a glimpse of its many dimensions. Dan Iancu, who you heard from earlier, reflects on what unites these different subjects.

Dan Iancu: There’s a risk that when one thinks about analytics or these type of more, let’s call them mathy or engineering topics, one can view them as entirely engineering processes, like completely correct systems, predictable. But if you think about the real world, it’s almost always a social system. It’s not just an engineering problem. There’s a lot more of people’s perspectives or people’s priorities or people’s incentive. So I would say what … Obviously in OSM, we cannot do too much of that, but we try to bridge a little bit the engineering side of things and the math side of things with the more social side of things. And here, while I’m thinking of the more social side of things, interpersonal skills and people dynamics and organizations, all of these other classes that the GSB talk a lot about, the human element, whether it’s on a micro scale or more on a macro scale like a human in an organization. And those are very important processes. If you think about, again, the real world problem, because the real world problem is rarely only an engineering problem,

Kevin Cool: Change lives, change organizations, change the world. Stanford Seed is a major international effort to bring GSB faculty and their expertise to entrepreneurs across Africa, Indonesia, and South Asia. The result of an extraordinary gift from Stanford GSB alum, Robert King, MBA class of 1960, and his wife Dorothy King, Stanford Seed aims to spur job creation, support research focused on alleviating poverty, and inspire students to become more globally engaged leaders. Darius Teter is its executive director.

Darius Teter: So what we do is we provide world-class business training and resources to founders and CEOs in emerging markets. And the goal is to help them make their businesses more resilient, to help them imagine a bold vision for growing that business, and then to execute on that vision. That’s what we do. So you could think of it as we try to take everything we’ve learned at the GSB about how to lead, how to build a business, and we try to take that to markets that typically don’t have that kind of access.

Kevin Cool: Darius believes the effects ripple outward.

Darius Teter: The simple truth is that people building businesses is the backbone of every successful economy. You’ve got the Walmarts and the Amazons of the world, but they’re not the ones who create the new jobs and a lot of the innovation too. And that was a real, for me, that was a really watershed realization, is that … And those small businesses in places like Nigeria or Tanzania or India, they face the credible hurdles, technology hurdles, access to network hurdles, access to finance, basic business practices, leadership, kind of stuff that we take for granted as our core curriculum is often not easily accessible or available to somebody who’s got a 30-person business in Cote d’Ivoire.

Kevin Cool: I’ve often felt that the GSB is an optimistic enterprise, and Seed may be one of its most ambitious initiatives. Darius also sees this forward-thinking mindset in the school’s current leadership.

Darius Teter: I joined not long after Jon Levin became dean, and he was and is an inherently optimistic guy. I mean, I think that flowed down through the school. He always saw the potential, the bright side, and Sarah Soule, the new dean, has taught for us for years. And I can tell you, she brings that same mindset in spades. I mean, I don’t think we get to see her for another five years, but when she was teaching for us, every single time she taught for us in every part of the world, she got a standing ovation. And what she brought was this optimistic sense that you can do this. You can build your business. You can succeed as a leader, even if it’s not something you instinctually feel good about. And so that inherent optimism, I think, flows from the leadership of the school first and foremost.

Kevin Cool: In every classroom and in every program, the GSB’s mission is the same, to prepare students to lead in a world that’s complex, unpredictable, and deeply connected. Perhaps what unites these courses and the people who teach them is a belief that learning here isn’t just about ideas. It’s about what those ideas make possible. From modeling and the language of business, to ethics and empathy, learning here begins with people, curious students, devoted faculty, and a community built on connection and purpose.

Suzie Noh: I think what makes the GSB so special is the students that we have. I’m always amazed at how curious they are, not just asking follow-up questions or clarifying questions about what I taught in class, but they go out and proactively do their own research to apply what we learn in class to the real world. The faculty here really want to help students learn. They invest a lot of time developing new classes, updating the materials for their classes to help the students have a better learning experience. I think we have incredible support from the admin, and we have a lot of staff members who are committed to supporting students, providing the tools and resources that they need.

And always, when I teach a class, I always tell myself that, “Oh, the students here are so lucky. They’re getting so close to all these extraordinary brilliant scholars that they can learn from.” And then the staff are really committed to helping them. So I cannot really pick one thing that makes GSB so special, but it’s I guess a mix of all these people, different members of GSB and their hard work that make this place so special.

Kevin Cool: On the next and last episode of GSB at 100, we’re going to Frost Amphitheater for the sounds from a once-in-a-lifetime celebration. You’ll also hear from students, alumni, and a few retired professors like change maker, Joanne Martin, who was the first female professor to receive tenure at the GSB.

Joanne Martin: When you tell the story of what’s wonderful in the business school, some of these achievements were hard fought, and if you don’t include a little taste of that, then you don’t get a sense of the difficulty of what the faculty have achieved over the years.

Kevin Cool: A special thanks to all those who made this podcast possible, and thank you for listening.

Ed deHaan: Several years ago, I had a student, graduated and went to Nike, and there’s a couple of terms in my class, debit and credit, and you don’t need to know what they are. But in accounting, debits are on the left and credits are on the right, and she sent me a custom pair of Nike shoes and on the left said, debit, and on the right said credit. And I still wear them to this day when in teaching, just for teaching, my special teaching shoes.